Most iOS games are either portrait-only or landscape-only. The AIR application descriptor file lets you easily specify this. All you have to do is add the following to your descriptor file, inside the initialWindow tag:

<aspectRatio>landscape</aspectRatio>

<autoOrients>false</autoOrients>

The above configuration will result in a landscape app that will be right-side up when the home button is on the right – known as “landscape right” – that doesn’t rotate to portrait when the device is turned. However, it will ALSO not rotate when the device is turned to “the other landscape orientation” – if you position your iDevice so that the home button is on the left, your app will be upside-down!

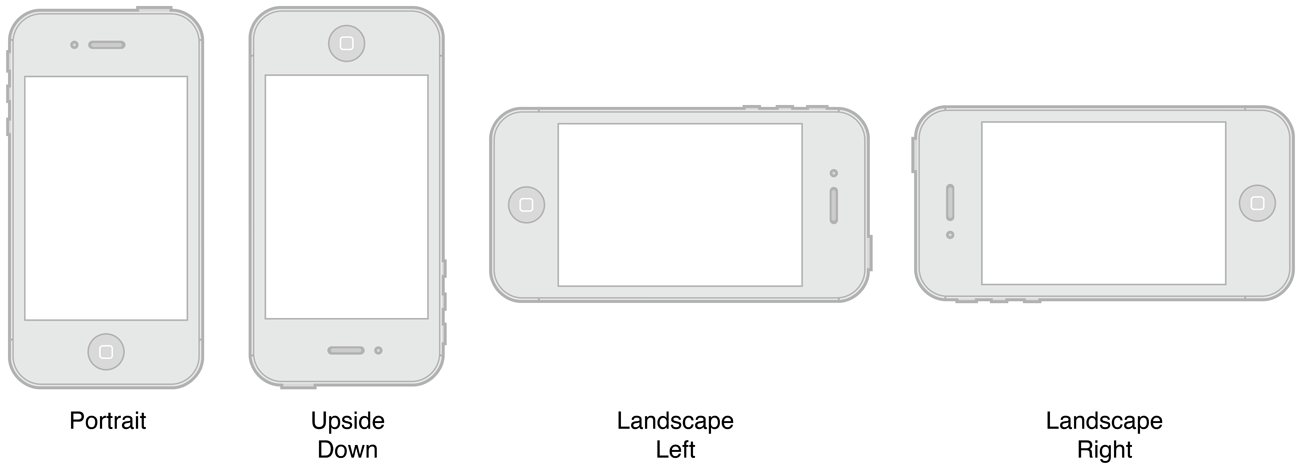

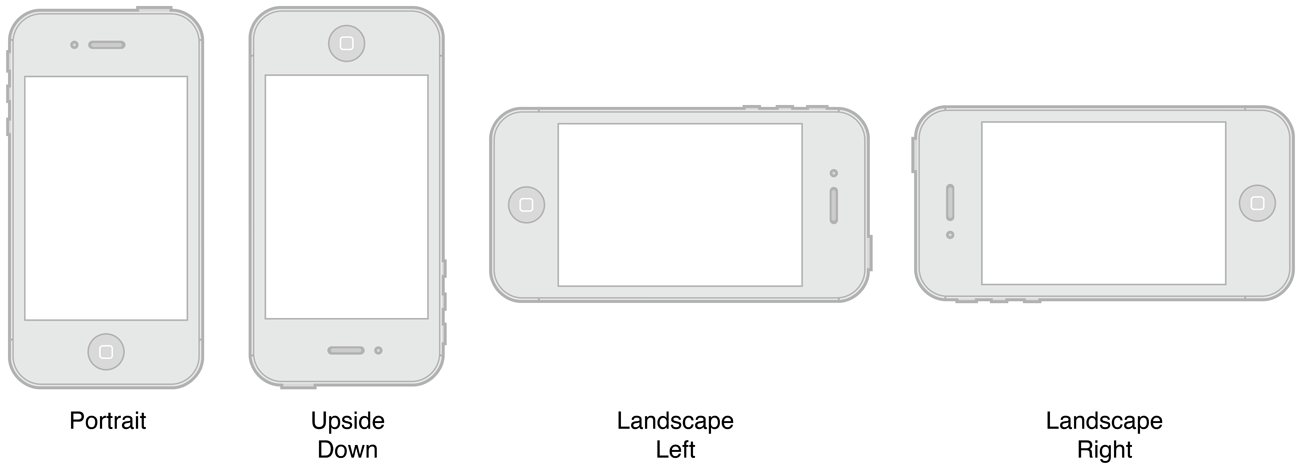

To have a truly industry-standard game, you’ll want your portrait games to support both “Default” and “Upside Down”, and your landscape games to support both “Landscape Left” and “Landscape Right”, as Apple calls them:

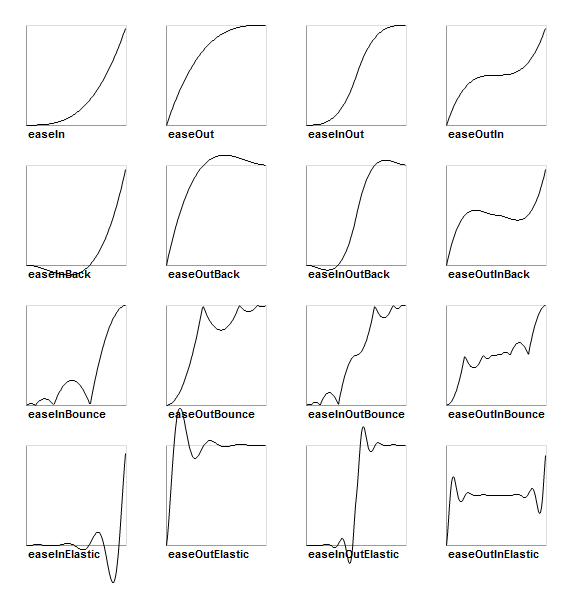

To accomplish this, we need to think about the concept of “stage orientation” as opposed to “device orientation”. Adobe’s StageOrientation class defines four orientations – DEFAULT, ROTATED_LEFT, ROTATED_RIGHT, and UPSIDE_DOWN. These orientations describe the orientation of the Flash stage relative to the physical device. DEFAULT simply means that the stage is oriented to match the physical orientation of the device. ROTATED_RIGHT and ROTATED_LEFT mean the stage is rotated either 90 degrees right or left. UPSIDE_DOWN means the stage is rotated 180 degrees.

For our game to work properly, we want to allow the stage to be in either the DEFAULT or UPSIDE_DOWN orientations, but NOT the ROTATED_LEFT or ROTATED_RIGHT orientations. Fortunately, Adobe has added some events that help us do just that. If your app descriptor has autoOrients set to true, the StageOrientationEvent.ORIENTATION_CHANGING event will be broadcast when the device’s accelerometer has detected the physical orientation has changed, and the Stage is about to rotate to follow suit. If you call Event.preventDefault(), you will prevent the Stage from rotating. So all we have to do is disallow rotating to the left or right, and allow rotating to the upside-down or default positions.

To accomplish this, add the following to your application descriptor file, to enable the Stage to rotate to follow the device’s physical orientation:

<autoOrients>true</autoOrients>

And add this to your app’s main class, to only allow a subset of those rotations to actually take place:

// we can control which orientations we want to allow with the following code

stage.addEventListener(StageOrientationEvent.ORIENTATION_CHANGING, onOrientationChanging );

function onOrientationChanging( event:StageOrientationEvent ):void

{

// If the stage is about to move to an orientation we don't support, let's prevent it

// from changing to that stage orientation.

if(event.afterOrientation ==

StageOrientation.ROTATED_LEFT || event.afterOrientation ==

StageOrientation.ROTATED_RIGHT )

event.preventDefault();

}

And voila! Your app now support both portrait orientations, or both landscape orientations!

Condensed from http://www.adobe.com/devnet/flash/articles/screen_orientation_apis.html

Also helpful: https://developer.apple.com/library/ios/featuredarticles/ViewControllerPGforiPhoneOS/RespondingtoDeviceOrientationChanges/RespondingtoDeviceOrientationChanges.html